Review About Role of Dentists in Opioid Crisis

Abstruse

The dental profession represents a significant player in the hereafter trajectory of the current opioid crunch. Exercising sound clinical judgement and adhering to evidence-based principles of pain management are essential. The aim of the nowadays report is to review the current landscape of the opioid crisis and present prove-based acute hurting management strategies in dentistry.

The Electric current Opioid Crisis

Prescribing opioids in the management of acute and chronic pain is a mutual practice in Due north America and across Ontario. 1-3 In fact, Canadians are the second largest per-capita users of prescription opioids worldwide. four The opioid crisis in Canada presents a major public wellness business organization that has been attributed to the widespread use of prescription opioids to care for non-cancer hurting. 5,six Ane in eight patients in Ontario are treated with opioids to manage pain. one College rates of opioid administration accept been closely associated with an increase in adverse events, including motor vehicle accidents, the development of opioid use disorder, low, opioid overdose, and expiry. seven-ten The rate of opioid-related deaths in Ontario has tripled between 2000 and 2015. In 2015, one in every 133 deaths in Ontario was opioid-related, with this burden being the largest among immature adults aged 15 to 24 years where one in every half-dozen deaths was opioid-related. 11 In 2016, 1 in three opioid-related deaths occurred among people with an active opioid prescription and more than 75% of opioid-related deaths had an opioid dispensed within the past three years. 12 Thus, prescription opioids are a meaning contributor to the ongoing opioid crisis in N America.

Health Quality Ontario (HQO) reported that dentists prescribe 16.half dozen% of all opioids in Ontario when compared to other healthcare professionals. two Following family physicians, dentists represent the second largest group of opioid prescribers in Ontario. ii Almost 75% of dentists' opioid prescriptions are new starts, which includes individuals who accept not filled an opioid prescription in the past half-dozen months or those who are being exposed to opioids for the outset time. It has been demonstrated that dentists represent a significant source of initial exposure to opioids. xiii In 2016, Hydromorphone contributed to 0.7% of opioid new starts prescribed past dentists while Tramadol deemed for 3.2% of the total new starts by dentists. Codeine combination prescriptions, such as Tylenol 3, were responsible for 80% of all new starts, a tendency that remains consistent. 2 This is concerning, as opioid use disorder often occurs from an initial chance exposure to prescription opioids. 5, 14 In fact, prescription opioid use before 12th course has been shown to significantly predict time to come opioid misuse post-obit high school. 15 Information technology is evident that dental professionals take an important role to play in the ongoing opioid crisis, and that practicing evidence-based hurting management strategies can positively bear on the future trajectory of this crisis.

Several policies and legislations have been implemented in the healthcare sector in efforts to combat the opioid crisis. The Narcotic Safety and Sensation Act (NSAA) is provincial legislation that was implemented in 2011, outlining certain requirements that the patient, prescriber, and dispenser must follow when accessing monitored drugs. A monitored drug is considered a controlled substance under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA) and other opioid medications not listed in the CDSA, such as Tramadol and Tapentadol containing products. The aim of this act is to reduce the corruption, misuse, and diversion of monitored drugs through the promotion of appropriate prescribing and dispensing practices. 16 Safeguarding our Communities Act was implemented at the provincial level in 2016 and mandates a fentanyl patch-for-patch exchange arrangement. In club for dispensers to release some other fentanyl patch to a patient, the previously used patch must be returned. 17 Further, the narcotic monitoring system (NMS) is a central database to review drug prescribing and dispensing activities in the community healthcare sector. This system contains real-time Drug Utilization Review (DUR) that volition exist performed each fourth dimension a dispensing record is submitted to the NMS by a chemist's. If issues such as double doctoring or polypharmacy are detected, the NMS will notify the pharmacy in real-time as the prescription is existence dispensed. These safeguards signal a growing effort to resolve the opioid crisis beyond all healthcare professions. In dentistry, sound prescribing practices can aid this overall effort to combat the opioid crisis.

Acute Pain in Dentistry

Background

In the 1970s, Steve Cooper and William Beaver developed and validated a tertiary molar removal model that compared the efficacy of different oral analgesics and a placebo control arm. 18 The third tooth removal model studied the subjective feel of pain effectively for several reasons. 3rd molar removal is a commonly performed procedure that causes similar surgical trauma for the bulk of patients, making the hurting feel relatively ubiquitous. This allows the sample size to exist big while minimizing individual variations in the hurting experienced by each patient. The procedure is often performed in both the left and right sides of a patient's oral cavity, allowing carve up-rima oris designs to be utilized to farther minimize subjective pain experience. Additionally, third molar removal is performed in young healthy adults which helps rule out several misreckoning variables in an experimental setting. In their hallmark study, Cooper and Beaver demonstrated that Ibuprofen (400mg) was more than efficacious than Codeine (60mg), Aspirin (650mg), or both analgesics in combination.xviii Clinical trials have consistently demonstrated that non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), administered every bit sole agents, are effective in the direction of mail service-operative dental pain. xix-22 Moore et al. (2018) demonstrated that 600mg of Ibuprofen resulted in the highest proportion of patients who experienced hurting relief, followed by 400mg Ibuprofen combined with 1000mg Acetaminophen. 23 Understanding the relevant findings in the literature, general prescription principles, and treatment algorithms or guidelines will assistance clinicians in making informed hurting management decisions.

General Principles

General principles must be adhered to for adequate pain management. Information technology is prudent to never administer a drug without an indication. Clinicians must residual the benefits and risks, and only continue if the rest is favourable. Moreover, all drugs have the potential to crusade drug interactions and adverse drug reactions. The get-go alternative to hurting direction should include non-pharmacological methods. If possible, the source of the pain should be eliminated straight. In dental do, this includes root culvert therapy, extraction, or incision and drainage. Analgesics help to mitigate pain, just do not eliminate pain. For acute mail service-operative dental pain, the apply of analgesics should be individualized to each patient based on their medical history and level of pain experienced. Other factors to consider when prescribing include allergies, intolerances or prior adverse drug reactions, pregnancy and lactation, likewise as hepatic and renal function. Dentists should avoid prolonged use of any analgesic amanuensis. The duration of post-operative dental pain is typically express to three to five days.

Management of Acute Dental Pain

An algorithm has been established in order to exercise best prescribing practices. 24 For the management of acute dental hurting, opioids are seen as third-line therapy following Acetaminophen and NSAIDs, and should only be considered by the clinician once the dosages of the not-opioids take been maximized.

Acetaminophen is the first drug of option and should e'er be considered from a take chances-benefit standpoint, particularly when pain severity is expected to be balmy to moderate. An adult dose of Acetaminophen is initially considered (Tabular array 1; 500-i,000mg q4h, maximum 4g/solar day). If 1,000mg of Acetaminophen is determined to be insufficient for constructive analgesia, and the patient has no contraindications to NSAIDs (Table 2), the side by side footstep is to recommend an NSAID (Ibuprofen 200-400mg q4-6h, every bit needed for pain). However, if the patient has a contraindication to NSAIDs (Table 2), adding codeine to Acetaminophen may be indicated. If the pain remains severe and more analgesia is required following the initial NSAID prescription, the maximum dose of NSAID is prescribed (Ibuprofen 600mg), or a combination of ane,000mg of Acetaminophen and 400mg Ibuprofen is considered. 25,26 Alternatively, adding an opioid (thirty-60mg codeine or v-10mg oxycodone combination) to the NSAID or Acetaminophen may also be considered. The clinician must optimize the dose and the frequency to ostend that compliance is not the underlying reason for inadequate pain relief prior to adding an opioid.

Table 1

Management of Acute Dental Pain: Acetaminophen and NSAIDs

Notation. NSAIDs are listed in decreasing selectivity for COX-2/increasing selectivity for COX-1 (with the exception of Floctafenine/Idarac)

Table 2

Indications, Furnishings, and Contraindications for Acetaminophen, NSAIDs and Opioids

Adapted from Haas 2002.24 Therapeutic furnishings of each analgesic agent are numbered. The primary therapeutic effects utilized in dentistry are analgesia and anti-inflammation.

If the clinician anticipates severe mail service-operative hurting prior to the process based on the nature of the procedure or the patient's hurting threshold, a pre-operative dose, loading dose, or effectually-the-clock dosing of NSAIDs may be indicated. Pre-operative NSAID dosing has been demonstrated to subtract the severity and onset of acute postal service-operative dental pain. 27 Still, loading doses are generally favoured, as pre-operative NSAIDs are best avoided when bleeding concerns exist. 24 A loading dose is merely two tablets stat, immediately later on the process, followed by i tablet every 4-six hours as needed for pain. The purpose is to reach steady state levels of NSAIDs prior to the dissipation of the local anaesthesia that was initially administered. An alternative dosing regimen for severe pain is around-the-clock for the first ane to three days, which aids in managing hurting prior to its onset. Long-duration local anaesthetics such as 0.v% Bupivacaine can be utilized at the cease of procedures to provide prolonged post-operative analgesia. 28 This arroyo results in a reduced demand for post-operative opioids. 29 Clinical judgement is required in each clinical scenario to determine if a pre-operative dose, loading dose, or around-the-clock regimen of NSAIDs is appropriate.

There are different reasons one may experience pain relief following the assistants of an analgesic. It is possible that the drug was efficacious and responsible for the alleviation of pain. However, the temporal relationship between the administration of the drug and the dissipation of pain may requite patients reason to believe the drug was effective when, in fact, the pain would have abated without whatever analgesics to brainstorm with. Another reason for pain relief is the placebo effect whereby no pharmacological effect exists. It is purely a psychological effect that accounts for the alleviation of pain. For example, patients often presume that more expensive drugs and prescribed drugs inherently have greater efficacy. Clinicians may prescribe 400mg of Ibuprofen rather than instructing the patient to buy it over-the-counter, as it may result in a psychological benefit to pain relief.

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen is the first alternative considered for post-operative dental pain in elderly, developed, and paediatric patients due to its favourable take chances-benefit profile. 24 Acetaminophen is effective for balmy to moderate pain, providing both analgesic and antipyretic properties without the gastric side effects of NSAIDs. 24 Information technology is of import to inform patients to avert other Acetaminophen-containing preparations such as Midol© or NyQuil©, as this may cause inadvertent overdose. Acetaminophen toxicity has been demonstrated when daily doses of 4,000mg are exceeded. thirty Hepatotoxicity has besides been reported in febrile pediatric patients as a issue of several dose miscalculations and subsequent administration by the parents. 31

Approximately 95% of Acetaminophen detoxification is accomplished by glucuronidation and sulfation, with these metabolites undergoing rapid renal elimination (Fig. 1). Under normal circumstances, a minor percentage (v%) of Acetaminophen is oxidized by cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYP2E1) into N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), a potentially toxic metabolite of Acetaminophen. This does not atomic number 82 to hepatotoxicity in healthy individuals, as NAPQI is conjugated and inactivated by glutathione. 32 When excessive amounts of Acetaminophen are consumed, the conjugation pathways (glucuronidation, sulfation, glutathionylation) become saturated and NAPQI accumulates, leading to pregnant hepatotoxicity. 33-35 N-acetylcysteine is the antidote of choice for Acetaminophen toxicity. It must exist administered prior to the clinical symptoms of overdose, typically inside the starting time sixteen hours of consumption. 22,35 It is important to empathize that so long as correct dosing instructions are provided past the clinician, the likelihood of agin reactions is generally depression. 36

Fig. 1

Metabolism of Acetaminophen. The majority of Acetaminophen is conjugated and eliminated in the urine (green arrows). A small per centum of Acetaminophen is converted into toxic N-acetyl-p-benzoquinoneimine (NAPQI), which may lead to hepatotoxicity (red arrows) when conjugation pathways are saturated due to excessive Acetaminophen consumption.

Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

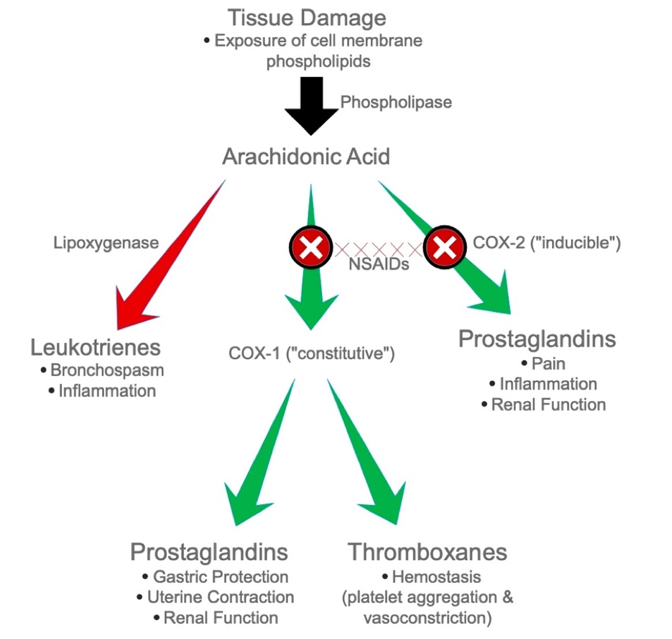

NSAIDs inhibit the action of cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2 enzymes (COX-1 and COX-two) in the bloodstream, decreasing the product of prostaglandins, thromboxanes, and prostacyclin (Fig. 2). Aspirin irreversibly acetylates COX-1 and COX-2, resulting in decreased levels of prostaglandins and thromboxane A2. 37 COX-1 is constitutively expressed and produces prostaglandins, which provide gastric protection, regulate renal blood flow, and stimulate uterine wrinkle. COX-1 too aids in hemostasis by producing thromboxane, a potent vasoconstrictor and initiator of platelet aggregation. COX-ii is induced during dental procedures that inflict cellular harm, augmenting the production of prostaglandins that mediate pain and inflammation.

Fig. 2

Arachidonic Acrid Cascade. Patients who are exceedingly susceptible to COX-1 and COX-2 occludent display signs and symptoms of anaphylaxis due to shunting of arachidonic acid through the lipoxygenase pathway (red arrows).

NSAIDs produce both therapeutic and adverse effects when COX-1 and COX-2 are blocked. In contrast to Acetaminophen, NSAIDs accept several drug interactions such as reducing the efficacy of antihypertensives, potential toxicity when combined with Lithium and Methotrexate, and increased bleeding with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other anti-platelets, all of which crave boosted management considerations (Table 3). NSAIDs are indicated for their analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and anti-pyretic properties. Agin effects and contraindications of NSAIDs are listed in Table 2. By inhibiting COX-1, the cytoprotective effect of prostaglandins is lost, and the patient is more susceptible to dyspepsia, which may lead to serious side furnishings such as gastric mucosal damage and bleeding. In fact, 16,500 deaths in the U.s.a. are attributed to gastric bleeding induced past NSAIDs. 38 Further, decreased thromboxane product leads to impaired hemostasis, rendering the patient susceptible to increased bleeding. Patients with a history of renal disease may develop renal damage following NSAID use. A patient may have an Aspirin (ASA) allergy, or an allergic-like reaction, otherwise known as an anaphylactoid reaction. In this case, arachidonic acid is shunted towards the leukotriene pathway, causing bronchospasm and other symptoms mimicking anaphylaxis that tin be extremely severe and life threatening (Fig. two). The adverse effects of NSAIDs are often dose and duration dependent. Thus, information technology is recommended to utilize the lowest effective dose for the shortest possible duration to eliminate acute pain. 39

Table 3

Mutual Drug Interactions with NSAIDs

Note. This list of drug interactions is not consummate

Opioids

The primary indication for the employ of opioids in dentistry is for their analgesic backdrop. Opioids have a profound ability to raise pain threshold and alter pain reactions, both of which contribute to incredibly constructive analgesia. Opioids have the potential to give patients a euphoric feeling, which may contribute to the analgesic effect. However, many other pharmacological effects may outcome post-obit assistants, including respiratory depression, sedation, hypo- and hypertension, nausea, vomiting, constipation, and urinary retentivity (Table 2). The development of tolerance, concrete dependence, and addiction require special consideration. Tolerance may develop chop-chop and can be seen in patients post-obit weeks of repeated intake, where higher doses are required in order to achieve the same analgesic effect. A land of physical dependence results when an individual requires a drug for the maintenance of normal homeostasis. Later discontinuation of the drug, the patient experiences withdrawal symptoms such every bit rhinorrhea, piloerection, abdominal cramps, diarrhea, restlessness, shivering, excessive perspiration, increased blood pressure level and insomnia. Studies have indicated that patients who take opioids for longer than vii days are more than probable to become physically dependent. forty Drug abuse is the inappropriate utilize of a drug for non-medical reasons and can lead to behavioural and concrete dependence if sustained. Above all, an opioid addiction may develop. 41 In addiction, the patient continues to crave opioids regardless of their known negative consequences and adverse furnishings. Clinicians must be enlightened of the signs that indicate aberrant drug related behaviours. Patients who request higher doses, complete analgesic regimens far too early on, "lose their pills frequently", and alter the route of delivery should be monitored closely by the clinician. The extensiveness and severity of these side effects elicited by opioids has led to the current opioid crunch.

Although opioid analgesics are not beginning-line agents for managing acute pain in dentistry, at that place are situations in which they are indicated and necessary. Three opioids that are nigh ordinarily prescribed in dentistry are Codeine, Oxycodone, and Hydromorphone (Table 4). Prescribing opioids should only be considered when in combination with Acetaminophen or an NSAID, at specified doses and intervals (Table 4). When an opioid is indicated, Codeine is the first opioid to consider. Formulations that combine Acetaminophen with Codeine are normally utilized (Table 5). If codeine is adamant to be insufficient, Oxycodone is the side by side opioid to consider. Oxycodone is combined with Acetaminophen (Percocet) or ASA (Percodan), and is deemed to be more effective than Codeine. Hydromorphone plays an of import part for patients with severe chronic pain, and thus is rarely used in a dental setting to manage acute pain. Combination drugs have become popular due to ease of administration, only do not follow the basic principle of maximizing non-opioids prior to administering opioids. For instance, the Tylenol 4 preparation contains 300mg of Acetaminophen and 60mg of codeine (Table 5), maximizing only the opioid dose with a sub-therapeutic amount of Acetaminophen.

Table 4

Commonly Utilized Opioid Analgesics in Dentistry

Table 5

Common Acetaminophen Combination Preparations

As information technology has become a common do in dentistry to routinely prescribe opioid combinations to manage post-operative pain. The Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario (RCDSO) outlined factors that may be contributing to the over-prescription of opioids. 42 Dentists may be overprescribing opioids out of addiction, convenience, or simply lack of cognition regarding the efficacy of non-opioid analgesics. Patients may need or expect the dentist to prescribe opioids, and it has been suggested that dentists are prescribing opioids in situations when they are not indicated in hopes to avert conflicts with their patients. The reasons for over-prescribing outlined by the RCDSO tin be avoided with measures aimed at educating both clinicians and patients alike. The RCDSO has indicated that merely a minority of the most severe clinical cases require opioid analgesia. 42

Guidelines for Opioid Management

In 2015, RCDSO published an opioid prescribing guideline that outlines the management of hurting in dentistry. Sequential steps demand to exist taken in order to minimize prescription opioid abuse. Prior to prescribing an opioid, is information technology prudent to consider whether the patient's pain is well documented, if an opioid is currently beingness taken, if signs of substance misuse, corruption, and/or diversion may exist inferred from their medical history, and to weigh the benefits and risks of prescribing an opioid. 42 If an opioid is to be prescribed, the recommended maximum number of opioid tablets that should be dispensed is illustrated in Tabular array 6.

Table 6

Commonly Utilized Preparations and the Maximum Number of Tablets Indicated

If the patient returns complaining of unmanaged pain following the first prescription of an opioid, a clinical reassessment, confirmation of diagnosis, and considerations regarding the effectiveness of the opioid need to exist deemed for prior to giving an increased dose of the opioid.

If the patient returns for a third appointment and is presenting with unmanaged pain, reassessment and confirmation of diagnosis must be repeated. At this point, a possible 3rd prescription may be issued. However, information technology is crucial to advise the patient that no further opioid prescriptions will be issued. Interprofessional collaboration must be utilized to address the pain management adequately and to forestall the potential for misuse, abuse, and/or diversion.

Special Populations

It is essential to individualize pharmacological regimens for all patients, peculiarly for patient populations that require special attending. A modification in the prescribed dose and frequency is often necessary for paediatric and elderly patients, equally well as for pregnant or breastfeeding mothers.

Paediatric Patients

In paediatrics, Acetaminophen is the showtime analgesic to consider, given at a dose of 10-15mg/kg q4-6h with a maximum dose of 75mg/kg. If further pain management is needed, Ibuprofen may be given as a liquid formulation at a dose of 10mg/kg q6-8h for children aged two-12, and 200-400mg q4h for children over 12 years former, with a daily maximum of i,200mg. ASA is contraindicated in paediatric patients due to their potential to cause Reye's Syndrome 42 Health Canada and the FDA do not recommend opioid prescriptions in patients anile 12 years or younger.

Elderly Patients

Canadians over the age of 65 make up xv% of the patient population, and account for over xxx% of pharmaceutical prescriptions. Information technology is projected that 25% of Canadians volition exist over the historic period of 65 in 2030. 44 Dentists must understand the pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic changes in elderly patients in gild to provide prophylactic and effective pharmacological pain direction. When possible, eliminating the source of pain using non-pharmacologic measures is prudent. If pharmacotherapy is required for hurting direction, Acetaminophen is the analgesic of choice. There are relatively minimal drug interactions with Acetaminophen, which is particularly important in elderly patients who may be currently taking multiple medications. 44 NSAIDs adversely effects the gastrointestinal tract by causing gastric bleeding, erosion, and ulceration, all of which may exist life threatening in the geriatric population. When an NSAID is indicated, the dose and duration should exist reduced. 44 In the instance where an elderly patient with a history of gastric bleeding is required to have an NSAID, the clinician should consider either administering the NSAID meantime with a prostaglandin analog such as misoprostol, or prescribing a COX-two inhibitor such as celecoxib, which has reduced gastrointestinal effects. Opioids are used every bit a last resort and should be avoided every bit elderly patients are more susceptible to their adverse furnishings. The depth and duration of the analgesic outcome of opioids is significantly increased in elderly patients. If an opioid is indicated, the dose should be prescribed at half of the recommended developed dose. 44

Pregnancy and Lactation

For a meaning patient, the first recommendation is to identify and eliminate the source of pain when possible. During pregnancy, patients are undergoing physiological changes that alter the pharmacokinetics of drugs, making some analgesics more appropriate to prescribe than others. When an analgesic is indicated, Acetaminophen is the drug of choice during all three semesters of pregnancy. The use of NSAIDs is less favourable and is a contraindication in the tertiary trimester every bit it causes increased bleeding, prolonged labour, and premature closure of the ductus arteriosus. NSAIDs may exist used cautiously in the 1st and 2d trimester, using the everyman effective dose for the shortest possible time. In general, opioids should be avoided during pregnancy. 45 However, if a pregnant patient is experiencing moderate to severe pain that cannot be managed by Acetaminophen, an opioid may be used in the 2d and 3rd trimester at a low dose for curt duration.

In the majority of instances, in that location is a negligible effect of most drugs on a nursing infant. Equally with pregnancy, the drug of choice during lactation is Acetaminophen. ASA may interfere with the infant's platelet office leading to increment haemorrhage and thus should be avoided. Opioids should too be avoided every bit they can cause extreme drowsiness in the nursing infant. 45

Conclusion

Prescription opioids go along to contribute to the ongoing opioid crisis. Equally mutual prescribers of opioids, dentists have a duty to assistance forestall its diversion, misuse, and abuse. Proper management of acute post-operative dental pain grounded in evidence-based principles is critical. Dentists are responsible for adhering to guidelines and individualizing post-operative analgesic care, while beingness cognisant of the fact that every opioid prescription has far reaching implications, affecting the current and future landscape of the opioid epidemic.

Oral Health welcomes this original article.

References

- Gomes, T., Pasricha, S., Martins, D. & Greaves, S., et al. Behind the Prescriptions: A snapshot of opioid utilize across all Ontarians. 1–22 (2017). doi:10.31027/ODPRN.2017.04.

- Wellness Quality Ontario. Starting on Opioids, Wellness Quality Ontario Specialized Study. (2018).

- Clark, D. J. & Schumacher, Yard. A. America's Opioid Epidemic: Supply and Demand Considerations. Anesth. Analg. 125, 1667–1674 (2017).

- Fischer, B. & Argento, East. Prescription opioid related misuse, harms, diversion and interventions in Canada: a review. Pain physician xv, (2012).

- Dhalla, I. A., Persaud, N. & Juurlink, D. North. Facing up to the prescription opioid crisis. BMJ (Online) 343, (2011).

- Boudreau, D. et al. Trends in long-term opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain. Pharmacoepidemiol. Drug Saf. xviii, 1166–1175 (2009).

- Bohnert, A. S. B. et al. Association between opioid prescribing patterns and opioid overdose-related deaths. JAMA – J. Am. Med. Assoc. 305, 1315–1321 (2011).

- Gomes, T., Mamdani, M. M., Dhalla, I. A., Michael Paterson, J. & Juurlink, D. N. Opioid dose and drug-related bloodshed in patients with nonmalignant pain. Curvation. Intern. Med. 171, 686–691 (2011).

- Scherrer, J. F. et al. The influence of prescription opioid apply elapsing and dose on evolution of treatment resistant low. Prev. Med. (Baltim). 91, 110–116 (2016).

- Engeland, A., Skurtveit, S. & Mørland, J. Risk of Road Traffic Accidents Associated With the Prescription of Drugs: A Registry-Based Cohort Report. Ann. Epidemiol. 17, 597–602 (2007).

- Gomes, T. et al. Measuring the Brunt of Opioid-related Bloodshed in Ontario, Canada. Journal of addiction medicine 12, 418–419 (2018).

- Gomes, T. et al. Contributions of prescribed and not-prescribed opioids to opioid related deaths: Population based cohort study in Ontario, Canada. BMJ 362, (2018).

- Pasricha, Southward. V et al. Clinical indications associated with opioid initiation for hurting management in Ontario, Canada: A population-based cohort written report. Pain 159, 1562–1568 (2018).

- Chou, R. et al. Opioids for Chronic Noncancer Pain: Prediction and Identification of Aberrant Drug-Related Behaviors: A Review of the Evidence for an American Pain Society and American Academy of Hurting Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline. J. Pain ten, (2009).

- Miech, R., Johnston, 50., O'Malley, P. M., Keyes, K. Yard. & Heard, Chiliad. Prescription opioids in adolescence and hereafter opioid misuse. Pediatrics 136, e1169–e1177 (2015).

- Ontario's Narcotics Strategy – The Narcotics Safety and Awareness Act – MOHLTC. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/drugs/ons/ons_legislation.aspx. (Accessed: 11th Jan 2020)

- Ontario Higher of Pharmacist's. Patch-For-Patch Fentanyl Return Program: Fact Sheet. (2018). Available at: https://www.ocpinfo.com/regulations-standards/practise-policies-guidelines/Patch_For_Patch_Fentanyl_Return_Fact_Sheet/. (Accessed: 11th Jan 2020)

- Cooper, S. A. & Beaver, W. T. A model to evaluate balmy analgesics in oral surgery outpatients. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. twenty, 241–250 (1976).

- Dionne, R. A. & Berthold, C. W. Therapeutic uses of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in dentistry. Critical Reviews in Oral Biology and Medicine 12, 315–330 (2001).

- Ahmad, Due north. et al. The efficacy of nonopioid analgesics for postoperative dental pain: a meta-analysis. Anesth. Prog. 44, 119–126 (1997).

- Dionne, R. A. & Gordon, Southward. 1000. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for acute hurting control. Dental Clinics of Northward America 38, 645–667 (1994).

- Hersh, E. V., Moore, P. A. & Ross, Thousand. L. Over-the-counter analgesics and antipyretics: A disquisitional assessment. Clin. Ther. 22, 500–548 (2000).

- Moore, P. A. et al. Benefits and harms associated with analgesic medications used in the management of acute dental hurting: An overview of systematic reviews. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 149, 256-265.e3 (2018).

- Haas, D. A. An update on analgesics for the management of astute postoperative dental hurting. J. Can. Paring. Assoc. 68, 476–482 (2002).

- Moore, R. A., Derry, S., McQuay, H. J. & Wiffen, P. J. Single dose oral analgesics for acute postoperative hurting in adults. Cochrane database Syst. Rev. CD008659 (2011). doi:ten.1002/14651858.CD008659.pub2

- Moore, P. A. & Hersh, Due east. V. Combining ibuprofen and acetaminophen for acute pain direction later on third-tooth extractions: Translating clinical research to dental practice. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 144, 898–908 (2013).

- Hersh, Eastward. V. et al. Prescribing recommendations for the treatment of acute hurting in dentistry. Compend. Contin. Educ. Paring. 32, (2011).

- Danielsson, Yard., Evers, H. & Nordenram, A. Long-acting local anesthetics in oral surgery: an experimental evaluation of bupivacaine and etidocaine for oral infiltration anesthesia. Anesth. Prog. 32, 65–8

- Jackson, D. 50., Moore, P. A. & Hargreaves, Thousand. M. Preoperative nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication for the prevention of postoperative dental hurting. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 119, 641–647 (1989).

- Guggenheimer, J. & Moore, P. A. The therapeutic applications of and risks associated with acetaminophen use: A review and update. Journal of the American Dental Clan 142, 38–44 (2011).

- Rivera-Penera, T. et al. Outcome of acetaminophen overdose in pediatric patients and factors contributing to hepatotoxicity. J. Pediatr. 130, 300–304 (1997).

- Haas, D. A. Adverse drug interactions in dental practice: Interactions associated with analgesics: Part 3 in a serial. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 130, 397–407 (1999).

- Turkoski, B. B. Acetaminophen: Quondam friend – New rules. Orthop. Nurs. 29, 41–43 (2010).

- James, L. P., Mayeux, P. R. & Hinson, J. A. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity. Drug Metabolism and Disposition 31, 1499–1506 (2003).

- Rumack, B. H. Acetaminophen hepatotoxicity: The showtime 35 years. in Journal of Toxicology – Clinical Toxicology forty, iii–20 (2002).

- Ouanounou, A., Ng, Thousand. & Chaban, P. Adverse drug reactions in dentistry. International Dental Journal idj.12540 (2020). doi:x.1111/idj.12540

- Vane, J. R. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis as a machinery of action for aspirin-like drugs. Nat. New Biol. 231, 232–235 (1971).

- Wolfe, Yard. M., Lichtenstein, D. R. & Singh, G. Gastrointestinal toxicity of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs. New England Periodical of Medicine 340, 1888–1899 (1999).

- Bally, Thousand. et al. Risk of acute myocardial infarction with NSAIDs in real world apply: Bayesian meta-analysis of individual patient data. BMJ 357, (2017).

- Dowell, D., Haegerich, T. M. & Chou, R. CDC guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain-United states, 2016. JAMA – J. Am. Med. Assoc. 315, 1624–1645 (2016).

- Olsen, Y. The CDC guideline on opioid prescribing: Rise to the challenge. JAMA – Periodical of the American Medical Association 315, 1577–1579 (2016).

- Royal College of Dental Surgeons of Ontario. Guidelines – The Role of Opioids in the Management of Acute and Chronic Pain in Dental Do. (2015).

- Ouanounou, A. & Haas, D. A. Pharmacotherapy for the Elderly Dental Patient. J Can Dent Assoc eighty (2015).

- Ouanounou, A. & Haas, D.A. Drug Therapy during Pregnancy: Implications for the Dental Practise. British Denta periodical. 220(8):413-417 (2016).

About the Authors

Mr. Andrew Lombardi is a 3rd year dental student at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Mr. Andrew Lombardi is a 3rd year dental student at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Ms. Sarah Lam is a 3rd year dental educatee at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Ms. Sarah Lam is a 3rd year dental educatee at the Faculty of Dentistry, University of Toronto.

Dr. Aviv Ouanounou† is an banana professor of Pharmacology and Preventive Dentistry at the Kinesthesia of Dentistry, Academy of Toronto, and is besides a clinical instructor and Treatment Plan Coordinator in the clinics. Dr. Ouanounou is the recipient of the 2014-2015 prestigious Dr. Bruce Hord Chief Teacher Honor for excellence in teaching and is the 2018-2019 Recipient of the W.W. Wood Award for Excellence in Dental Education Dr. Ouanounou is a Fellow of the International College of Dentists, the American Higher of Dentists and the Pierre Fouchard Academy. He is a fellow member of the American Academy of Hurting Management and the American College of Clinical Pharmacology. Dr. Aviv Ouanounou is the corresponding writer for this article and he can be reached at aviv.ouanounou@dentistry.utoronto.ca.

Dr. Aviv Ouanounou† is an banana professor of Pharmacology and Preventive Dentistry at the Kinesthesia of Dentistry, Academy of Toronto, and is besides a clinical instructor and Treatment Plan Coordinator in the clinics. Dr. Ouanounou is the recipient of the 2014-2015 prestigious Dr. Bruce Hord Chief Teacher Honor for excellence in teaching and is the 2018-2019 Recipient of the W.W. Wood Award for Excellence in Dental Education Dr. Ouanounou is a Fellow of the International College of Dentists, the American Higher of Dentists and the Pierre Fouchard Academy. He is a fellow member of the American Academy of Hurting Management and the American College of Clinical Pharmacology. Dr. Aviv Ouanounou is the corresponding writer for this article and he can be reached at aviv.ouanounou@dentistry.utoronto.ca.

RELATED ARTICLE: The Opioid Crisis

Source: https://www.oralhealthgroup.com/features/the-opioid-crisis-and-dentistry-alternatives-for-the-management-of-acute-post-operative-dental-pain/